While Antonín Dvorák is sometime considered as the greatest composer ever to have lived in the Czech Republic, in the eyes of the Czechs only one man deserves that epithet: Bedřich Smetana.

Smetana was born in 1824 into a fairly prosperous family as the son of a brewer. From a young age, Smetana excelled in music and he was sent away to study in Prague, where he indulged in the capital’s rich cultural life.

By the time that Smetana travelled to Pilsen in 1840, he had already composed for string quartet but he began to focus more on the piano. He considered his 3 Impromptus (1841) to be the real start of his career.

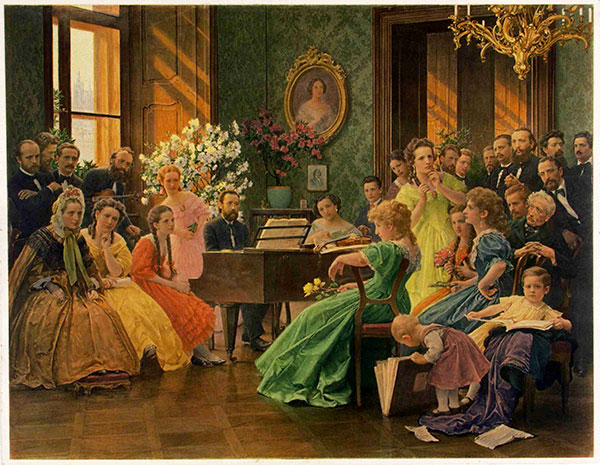

In 1844, Smetana began studying in Prague. He tried to earn a living as a piano teacher but hardly managed to make ends meet. However, Franz Liszt's acceptance of the dedication of his Opus 1 (1848) was encouraging. Smetana opened a music institute, which allowed him to continue teaching and save enough to start a family with Kateřina Kolářová.

The following years were marked by economic difficulties and a personal tragedy: the death of three of the couple’s daughters.

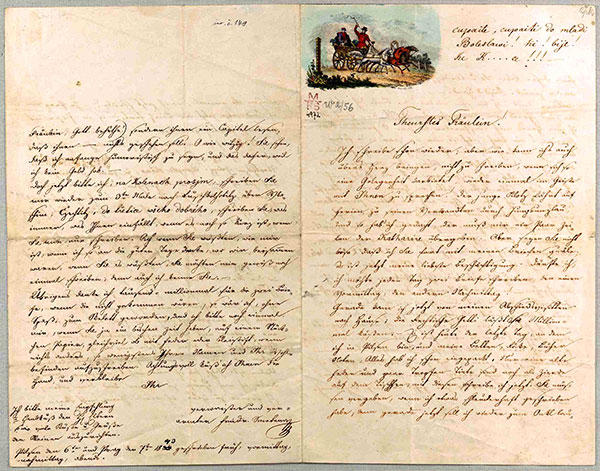

Miniature of Bedřich Smetana, 1880. Unknown

Národní muzeum, eSbírky. CC BY

Despite these misfortunes, Smetana dedicated himself to supporting a Czech national revival after the uprising in Prague. But when reforms failed to arrive, he moved with his family to Sweden, where he was offered a job in Gothenburg – the nation’s second-largest city.

The favourable impression of his early months in Sweden prompted Smetana to consider settling there for good. His wife’s poor health and his feelings of artistic isolation, however, made him decide to return to Prague in the spring of 1859. The journey ended in tragedy when his wife passed away during the trip.

Smetana married again and brought his second wife, Bettina Ferdinandová, to Sweden. His compositions from this time – such as the symphonic poems Richard III (1858), Wallenstein's Camp (1859) and Hakon Jarl (1861) – garnered much criticism. But Smetana remained focused on his masterplan: to make a big comeback in Prague.

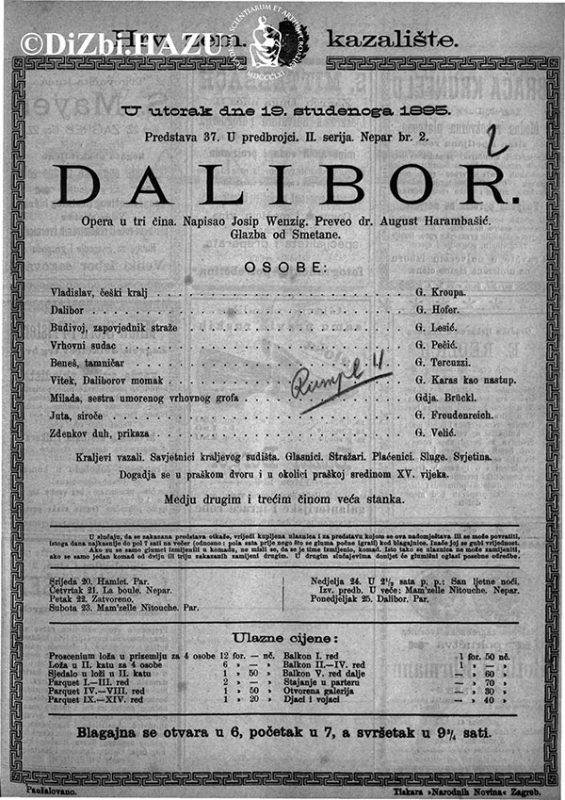

When the Provisional Theatre announced a contest for playwrights and composers, Smetana knew his moment of glory was near. He submitted the opera Brandenburgers in Bohemia (Braniboři v Čechách, 1866) and won the competition, instantly becoming a celebrity. At 42, his career had finally taken off. He became the Director of the Provisional Theatre, where he furthered the establishment of a ‘Czech national school’ while expanding the international repertoire as well. He himself continued writing opera’s such as Dalibor (1868) and Dvě vdovy (The Two Widows, 1874).

All in all, Smetana’s time as a theatre director was disputed but fruitful, resulting among others in the first plans for his magnum opus Má vlast (My Country, c.1872-9). This orchestral cycle, consisting of six symphonic poems, unfolds a narrative about the history, mythology and landscape of Bohemia. Navigating along mythical rock masses (Vyšehrad), Bohemian fields and forests (Z českých luhů a hájů) and the magical mountain Blaník, this was Smetana's 'multidimensional' portrait of his homeland.

The second movement Moldau (Vltava) in particular has entered the classical canon as one of the strongest exponents of Czech national style and a brilliant example of 'topographical music'. Má vlast launched Smetana to stardom and became a national hymn: a remarkable conclusion to a story of which the Swedish chapter is often forgotten.

Feature image: Bedřich Smetana, Josef Matthauser, Národní muzeum - České, CC BY

By Sofie Taes, KU Leuven

This blog post is a part of the Migration in the Arts and Sciences project, which explores how migration has shaped the arts, science and history of Europe.